Title: The Alphabet of Sacred Geometry

Author: Alloya Huckfield

Description: "Explore the fundamentals of sacred geometry: the point, line, circle, triangle, and square. Discover how these basic shapes form the foundation of nature, art, and architecture."

tags:

- Point

- circle

- triangle

- square

- geometry

- Monad

- Bindu

- Pythagorean

- sacred-geometry

icon: LiAsteriskthe-alphabet-of-sacred-geometry

Understanding Sacred Geometry begins with exploring the basic shapes that form the foundation of all complex geometric patterns in nature and design. These shapes appear as perfect proportions with deep symbolic meaning throughout the natural world and in humanity's greatest architectural works. They represent a visual language that connects mathematics, nature, and spiritual understanding across diverse cultures and time periods. The point, line, triangle, square, and circle serve as the alphabet of this universal language, creating a bridge between the measurable physical world and the intangible realm of meaning and consciousness.

Sacred geometry reveals itself in the spiral of a nautilus shell, the hexagonal chambers of a honeycomb, the branching patterns of trees, and the proportions of the human body. These same fundamental patterns appear in the architecture of ancient temples, cathedrals, mosques, and pyramids worldwide, suggesting that our ancestors recognized and honoured these recurring mathematical relationships as expressions of cosmic order. By studying these basic geometric forms, we begin to see the world through a different lens—one that perceives the mathematical harmony underlying all creation.

When we observe that the same proportions appear in structures built by civilizations separated by vast distances and time, we discover a compelling mystery: how did diverse cultures arrive at the same geometric principles? Perhaps these shapes represent something fundamental about reality itself—a hidden architecture that our ancestors intuited through careful observation of natural patterns. The study of sacred geometry thus becomes an exploration not just of shapes and measurements, but of the very ordering principles that govern both the physical universe and human consciousness.

As we progress through this chapter, we will examine each foundational shape in detail, starting with the simplest element—the point—and building toward more complex forms and relationships. Each geometric form carries multiple layers of meaning: mathematical, natural, and metaphysical. By understanding these basic building blocks, we prepare ourselves to comprehend the more intricate sacred patterns that have fascinated humanity for millennia and continue to influence contemporary design, art, and architecture today.

The Point

At the heart of sacred geometry lies a profound beginning - the simple act of placing a pencil on paper to create a point. This initial gesture, seemingly mundane, contains deep significance. Before any sacred geometric pattern can emerge - whether it's flower-of-life-the-vesica-piscis, the Vesica Piscis, or the golden-spiral - there must first be this singular point of origin. The point represents the most fundamental geometric concept: position without dimension. When we place our pencil on the blank page, we are creating the first bridge between the un-manifested world of potential and the manifested world of form. This dot becomes the center point from which all other geometric forms will emerge.

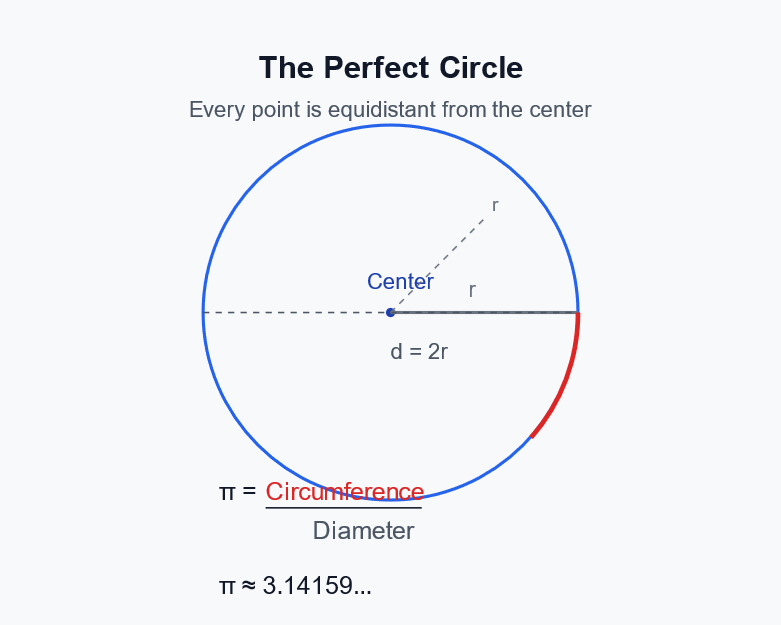

From this single point, we can extend outward in all directions equally to create a circle - the first sacred form that contains all potential within it. The circle cannot exist without first establishing its center point. This relationship between point and circle mirrors many spiritual traditions that speak of creation emerging from a singular source. In metaphysical traditions, the point symbolizes unity consciousness - the state of undifferentiated oneness that precedes all creation. It represents the monad in Pythagorean philosophy, the Bindu in Hindu traditions, and the divine singularity in various mystical systems.

The Bindu (Sanskrit for "point" or "dot") represents the primordial seed from which all creation emerges. In sacred geometric understanding, the Bindu is not merely a mathematical point but a profound cosmological concept with several key dimensions: The Bindu exists in a state of infinite potential—it contains everything in un-manifested form. It represents the moment just before creation begins, holding all possibilities within its seemingly dimensionless nature. This paradox is central to understanding the Bindu: though it appears as nothing, it contains everything.

In Hindu and Tantric traditions, the Bindu sits at the center of the sri-yantra and other sacred diagrams. Shiva (consciousness) and Shakti (energy). From this perspective, the Bindu serves as the bridge between the un-manifested absolute and the manifested universe. The Bindu also relates to consciousness itself. In meditation practices, particularly within yoga traditions, practitioners focus on the Bindu as a way to access pure awareness beyond form. The third eye chakra (Ajna) is sometimes represented as a Bindu, suggesting this point as a gateway to transcendent awareness.

The point serves as both beginning and end in sacred geometric creation—it is where the compass first touches the paper to begin a circle, and it is where complex patterns ultimately lead the consciousness back to unity. This primordial point contains within it all possibilities, all potentials, all futures - yet remains perfectly still and dimensionless. The dot also symbolizes the individual consciousness - our own center of awareness from which we perceive and interact with the world. Just as the geometric point serves as the reference for all measurements and relationships in sacred geometry, our consciousness serves as the reference point for our experience of reality.

In many spiritual traditions, meditation practices focus on returning awareness to this center point - the still, quiet center within that exists beyond time and space. Like the geometric point that has position but no dimension, this center of consciousness is said to be everywhere and nowhere simultaneously. The dot also represents the present moment - the infinitesimal yet eternal "now" that exists between past and future. In sacred geometry, all forms unfold from this present moment of creation, just as all geometric forms unfold from the initial point.

When we begin our sacred geometric drawings with this simple dot, we are participating in a symbolic act of creation that mirrors the emergence of the universe itself. We are acknowledging that all complexity, all pattern, all form must begin with unity. The humility of starting with this smallest element teaches us that the grandest structures in our universe - from galaxies to DNA - emerge from singular points of energy coming into relationship. As you progress in your understanding of sacred geometry, remember that each time you place that pencil on paper to begin a new construction, you are re-enacting the primal moment of creation - bringing forth order from emptiness, form from formlessness, and multiplicity from unity.

The mathematical point shares conceptual territory with the Bindu but has its own significance within Western sacred geometric traditions: A point in sacred geometry represents the dimension zero—it has position but no extension. It serves as the fundamental building block from which all other geometric forms arise. When a point moves, it creates a line (dimension one). When a line moves perpendicular to itself, it creates a plane (dimension two). This progression reveals how complexity unfolds from simplicity. The point represents unity before differentiation.

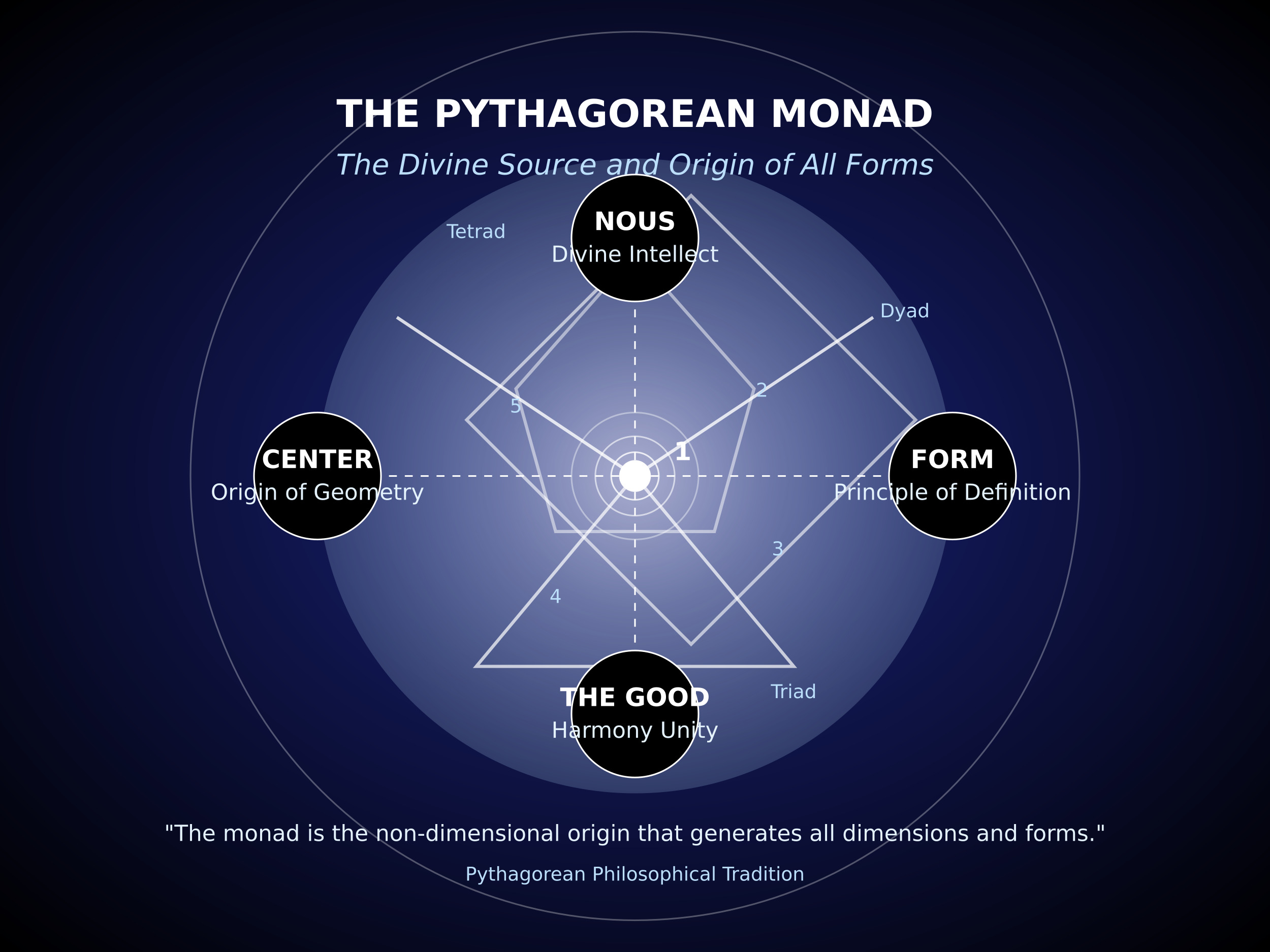

In the Pythagorean tradition, the monad (represented by a point) symbolizes the divine source—singular, indivisible, and the origin of all numbers and forms. In Pythagorean thought, the monad—represented by a simple point—serves as the primordial element of creation. The Pythagoreans considered it to be divine for several key reasons:

First, the monad is singular—it stands alone as the first unit of existence. Unlike other numbers that can be divided or combined, the monad remains fundamentally indivisible. This quality of indivisibility was seen as a reflection of divine unity.

Second, the monad functions as the generative source of all other numbers. The Pythagoreans viewed the numerical sequence as flowing from this single point: 1 creates 2, 2 creates 3, and so forth. This generative capacity mirrors the divine act of creation. The monad's significance extends beyond simple arithmetic. For the Pythagoreans, numbers were not merely quantitative tools but embodiments of metaphysical principles.

The monad represents several important qualities. The monad symbolizes wholeness and completeness as the number one. It establishes the principle of sameness that allows things to be recognized as themselves. Though singular, it contains within itself the potential for all subsequent numbers.

The monad represents several important qualities that have profound implications in philosophical and metaphysical traditions. The monad symbolizes wholeness and completeness as the number one. This unity is not merely a mathematical concept but represents the fundamental indivisible nature from which all else emerges. In many traditions, this unitary principle serves as both the origin and ultimate destination of all existence.

The monad establishes the principle of sameness that allows things to be recognized as themselves. This quality of identity is essential for coherent reality, providing the foundation for all logical systems and rational thought. Without this principle of self-identity that the monad represents, nothing could maintain consistent properties or be differentiated from anything else.

Though singular, the monad contains within itself the potential for all subsequent numbers. This generative capacity makes it not merely a static point but a dynamic principle. The monad doesn't just precede multiplicity—it contains multiplicity in seed form. This paradoxical aspect of the monad fascinates philosophers: how can absolute simplicity give rise to complexity? The answer lies in understanding that the monad's simplicity is not emptiness but rather a concentrated fullness.

In Neoplatonic philosophy, the monad was associated with the concept of "the One" from which all reality emanates. For Pythagoras and his followers, the monad represented not just a number but a metaphysical principle—the first cause and the essential building block of reality. Later, philosophers like Leibniz developed sophisticated monadologies where monads were understood as the fundamental substances of the universe, each reflecting the entire cosmos from its unique perspective.

The monad also serves as a powerful symbol in contemplative traditions, representing the reunification of consciousness with its source. The journey from multiplicity back to unity mirrors spiritual paths across various cultures, where the fragmented self seeks integration and wholeness.

The Pythagoreans developed a rich philosophical framework around the monad, attributing to it several profound qualities that reveal its central importance in their worldview. These attributes were not merely abstract concepts but formed the foundation of their understanding of reality itself.

Within Pythagorean thought, the monad was intimately associated with the intellect, or nous. They viewed the monad as the embodiment of pure thought and consciousness—the primordial awareness that precedes all differentiation. This intellect was considered divine in nature, representing the capacity for understanding that exists prior to any specific object of knowledge. Just as the monad generates all numbers while remaining distinct from them, the intellect comprehends all forms while maintaining its unified nature. This connection between the monad and nous influenced later philosophical developments, particularly in Neoplatonism, where the One was described as a transcendent intellect from which all reality emanates.

The Pythagoreans also understood the monad as representing form rather than matter. In their metaphysical system, form provided definition, structure, and meaning to otherwise undifferentiated matter. The monad, as the principle of form, gave shape and identity to the cosmos. This distinction parallels their understanding of odd and even numbers—odd numbers (beginning with the monad) were considered limited and defined, while even numbers represented the unlimited and indefinite. Through this association with form, the monad became the organizing principle that brought order to chaos, similar to how a geometric point defines and organizes space around it.

The Pythagoreans identified the monad with the principle of good. In their axiology, goodness was associated with unity, harmony, and proportion—all qualities that flowed from the monad. They believed that just as mathematics revealed perfect proportions and harmonies derived from simple numerical relationships, so too did ethical living involve achieving harmony within oneself. The monad represented this ideal harmony, the perfect balance that constituted goodness. This association between unity and goodness later influenced Plato's conception of the Form of the Good as the highest principle in his metaphysical system.

In Pythagorean geometry, the monad served as the center point from which all geometric forms emerge. They conceived of the point as having position but no dimension—a perfect representation of unity that nonetheless generates multiplicity. From this dimensionless center, lines, planes, and solids could be constructed, forming increasingly complex geometric structures. The Pythagoreans saw profound significance in this progression from simplicity to complexity, understanding it as a model for how the cosmos itself unfolds from a singular divine principle. The monad as geometric center also represented balance and equilibrium—the still point around which all motion occurs, again reinforcing its association with harmony and order.

These attributes were deeply interconnected in Pythagorean thought. The monad as intellect, form, goodness, and geometric center collectively expressed their understanding of a fundamental principle that was simultaneously mathematical, metaphysical, ethical, and cosmological. This unification of multiple domains of knowledge under a single principle reveals the holistic nature of Pythagorean philosophy, where mathematics was not separate from ethics or metaphysics but formed an integrated understanding of reality with the monad at its heart.

In Pythagorean cosmology, the monad serves as the model for the universe itself. Just as all numbers proceed from the monad, all beings proceed from a single divine source. This conception influenced later Neoplatonic ideas about emanation—the theory that all existence flows from and returns to a singular divine reality.

The geometric representation of the monad as a point also carries cosmological significance. From this dimensionless point, all other geometric forms can be derived: two points create a line, three create a triangle, and so forth. This progression mirrors the Pythagorean understanding of how complex reality emerges from simple principles.

The Pythagorean concept of the monad significantly influenced later philosophical traditions. Plato's Theory of Forms draws from these ideas about divine unity. Later, Neoplatonists like Plotinus developed the concept further, describing "The One" as the transcendent source of all being.

This mathematical-metaphysical framework established by the Pythagoreans remains influential in Western thought, providing an early model for understanding how multiplicity might emerge from unity and how abstract principles might structure physical reality.

The Circle ○

At its most basic level, the circle represents wholeness. Unlike shapes with corners or edges, the circle contains no beginning or end. Every point along its circumference exists in perfect relationship to the center. This mathematical property makes the circle a natural symbol for eternity, completion, and the absolute.

The circle, manifests abundantly in nature, from the grand celestial dance of planets and stars to the intricate, unseen worlds of cells and atoms. Water, the very essence of life, naturally forms circles in droplets and ripples on the surface of still ponds, symbolizing the unending flow and interconnectedness of al of creation. This shape is a testament to life's innate tendency towards unity and harmony.

The Pantheon in Rome stands as perhaps the most remarkable circular sacred structure in Western architecture. Its defining feature, the oculus—a perfect circular opening 30 feet in diameter at the dome's apex—creates a direct connection between earth and sky. This opening admits a concentrated beam of sunlight that traces a predictable path across the interior as the day progresses, functioning as both timekeeping device and cosmic connector. The Romans understood that this moving circle of light represented more than mere illumination—it symbolized the divine presence manifesting within human space.

This pattern of circular sacred architecture extends far beyond Rome. Consider the rotundas of Byzantine churches, where the circle represented divine perfection and eternity. The circular plans of these structures weren't merely aesthetic choices but cosmological statements—microcosms reflecting the macrocosm of creation. The dome above, often adorned with celestial imagery, represented heaven itself, with the circular base representing earth. The worshipper standing at the center occupied the The the-axis-mundi—the sacred center point connecting realms.

When we examine Byzantine rotundas and domed churches more closely, we discover a rich theological language encoded in their circular elements. Byzantine architects inherited the Roman mastery of circular construction but infused it with profound Christian cosmology. For Byzantine theologians, the circle represented divine perfection because it has no beginning or end—a perfect geometric expression of God's eternal nature. The circular plan allowed Christians to physically inhabit this theological concept, experiencing divine perfection through architectural form.

The Church of San Vitale in Ravenna offers a remarkable example. Its octagonal plan with a central circular space creates a transitional geometry—the octagon mediates between the square (representing earth) and the circle (representing heaven). As worshippers move from the square outer walls toward the circular central space, they physically participate in a journey from earthly reality toward divine perfection.

The Byzantine dome represents perhaps the most significant development of circular sacred architecture. In churches like Hagia Sophia, the dome doesn't merely cover the space—it becomes the central organizing principle for the entire structure. The dome's immense circular base (created by the ring of windows at its perimeter) seems to float mysteriously above the space, creating what contemporaries described as the impression of "heaven on earth."

Byzantine domes typically featured an image of Christ Pantocrator (the All-Ruler) at their apex, surrounded by concentric rings depicting angelic hierarchies, saints, and biblical scenes. This imagery wasn't decorative but pedagogical and theological—the dome became a cosmic map showing the divine order of creation. The worshipper looking upward could "read" this visual text, understanding their place within the greater cosmic hierarchy.

Byzantine architects employed sophisticated mathematical relationships in these circular forms. The ratio between the height of the dome and the diameter of its base often approximated divine proportions (what we now call the Golden Ratio. These mathematical harmonies weren't coincidental but intentional—they reflected the Byzantine belief that God had ordered the cosmos according to perfect mathematical relationships.

The pendentives—those triangular segments that allow a circular dome to rest on a square base—represent a remarkable geometric innovation that solved the ancient architectural problem of placing a round form atop a square one. This technical solution carried profound symbolic meaning, representing the reconciliation of heavenly perfection with earthly limitation.

Byzantine architects mastered the manipulation of light through circular forms. The ring of windows at a dome's base admitted light that seemed to emanate from heaven itself. As sunlight moves through these windows throughout the day, the interior illumination constantly changes, creating a dynamic experience that mirrors the living, breathing cosmos.

In churches like Hagia Sophia, thousands of gold tesserae (small mosaic pieces) in the dome reflect this light, creating a shimmering effect that dematerializes the massive structure. This visual phenomenon transforms solid architecture into something that appears to transcend physical laws—a perfect architectural expression of divine transcendence.

For the Byzantine worshipper, standing at the center point beneath the dome placed them at what religious historians call the axis mundi—the cosmic axis connecting heaven and earth. This positioning wasn't accidental but liturgically significant. During the Divine Liturgy, this central point became the location where heaven and earth were believed to intersect most powerfully.

The circular movement of priests and deacons around the altar during Byzantine liturgies reinforced this cosmic symbolism. Their circular processions mirrored the perceived movements of heavenly bodies and angelic beings, transforming ritual action into a participation in cosmic order.

The Byzantine approach to circular sacred architecture profoundly influenced other traditions. Russian Orthodox churches adopted and elaborated on Byzantine dome symbolism. Islamic architects, while avoiding figurative imagery, embraced and developed the cosmological dimensions of circular and spherical forms in mosque design. Even Western Gothic cathedrals, though emphasizing vertical lines and pointed arches, incorporated rose windows—massive circular openings filled with stained glass—that served as geometric expressions of divine perfection.

When we enter a Byzantine rotunda today, we experience something the original architects understood intuitively—circular architecture affects human consciousness differently than rectilinear forms. The absence of corners creates a sense of boundlessness. The perfect symmetry of the circle creates a peculiar acoustic phenomenon where sounds from different points converge at the center, creating what acousticians call "focusing effects." This sonic phenomenon reinforced the sense of the center as a place of special power and significance.

The circular plan also democratizes sacred space in a unique way. Unlike axial plans that create hierarchical distinctions between spaces closer to or further from an altar, the circle creates equal access to the sacred center from all directions. This architectural equality reflected theological concepts about equal access to divine grace—a literal concrete expression of abstract theological principles.

This sophisticated integration of theology, cosmology, mathematics, light, and human psychology within Byzantine circular architecture reveals why these forms have maintained their power to move us across centuries. They speak to something fundamental in human perception—our innate recognition of the circle as a symbol of completion, perfection, and divine order. In these sacred circular spaces, geometry becomes theology, and abstract cosmic principles become tangible, inhabitable realities.

In Islamic architecture, we find the circle expressed through intricate geometric patterns and in the domes of mosques. These domes often feature concentric circular patterns radiating from a central point, visually representing the universe emanating from divine unity. The circle here becomes a meditation on tawhid—the oneness of God that stands as the cornerstone of Islamic theology.

Islamic geometric patterns frequently use the circle as their foundation. These patterns develop through precisely dividing the circle and connecting points to create intricate designs. Craftsmen use a compass to draw perfect circles as the starting point for generating complex geometric compositions. These patterns often feature six-fold and eight-fold symmetry derived from circular divisions.

The mihrab (prayer niche) in mosques often features semi-circular arches adorned with circular and radial patterns. These designs help focus the worshipper's attention toward Mecca during prayer. Similarly, the minaret—the tower from which the call to prayer is announced—frequently incorporates circular elements in its cylindrical form and spiral staircases.

The concept of tawhid (the oneness of God) finds expression through circular geometry in Islamic architecture. The circle has no beginning or end, symbolizing eternity and divine unity. All points on a circle maintain equal distance from the center, representing the equal relationship of all creation to the Creator. When circles interconnect in Islamic patterns, they create a visual meditation on the interconnectedness of all existence while maintaining the primacy of divine oneness.

The muqarnas—stalactite-like decorative vaulting used in Islamic architecture—often incorporates circular forms arranged in three-dimensional compositions. These elements create a transition between square and circular spaces, representing the harmony between earthly and celestial realms.

Islamic calligraphy also employs circular compositions, particularly in designs called "daireh" (circle). Sacred texts arranged in circular patterns reinforce the concept of divine perfection and completeness expressed through both word and form. The mathematical precision in Islamic circular patterns demonstrates an understanding of geometric principles that predates many Western mathematical discoveries. These designs incorporate concepts like the golden ratio and elaborate tessellations based on precise circular divisions.

The circle's significance extends to ritual spaces as well. Stone circles like Stonehenge aligned with solar and lunar cycles, transforming circular architecture into astronomical calendars. The circle represents one of humanity's most fundamental symbolic forms, and its application in ritual spaces reveals our ancestors' sophisticated understanding of both astronomy and sacred geometry. Stone circles like Stonehenge demonstrate how ancient societies transformed circular architecture into precise astronomical calendars, creating spaces that connected earthly rituals with celestial patterns.

Stonehenge stands as perhaps the most famous example of circular ritual architecture with astronomical significance. Built in several stages between approximately 3000-1500 BCE, this monument's circular design wasn't merely aesthetic but functional. The stones were positioned with remarkable precision to mark critical celestial events:

The summer solstice alignment remains the most well-known feature, where the rising sun appears directly above the Heel Stone when viewed from the center of the circle. This alignment creates a dramatic visual effect as sunlight penetrates through the central trilithon archway, casting a beam precisely into the heart of the circle.

Less commonly discussed but equally significant is the winter solstice alignment, where the setting sun aligns with the center of the monument when viewed from the Avenue. These solar alignments effectively transformed the circular monument into a giant calendar marking the yearly cycle.

The sophistication of Stonehenge extends beyond solar observations. Researchers have identified probable lunar alignments within the stone arrangement that track the complex 18.6-year lunar cycle. The placement of specific stones appears to mark the extreme positions of moonrise and moonset, known as lunar standstills.

This lunar tracking capability demonstrates that circular ritual spaces served as multi-functional astronomical instruments, capable of measuring both solar and lunar cycles with remarkable accuracy. The builders understood that circular architecture provided the ideal geometric form for creating these calendrical functions, as the circle naturally reflects the cyclical patterns observed in celestial movements.

Stonehenge represents just one example within a global tradition of circular astronomical calendars. Throughout Europe, hundreds of stone circles demonstrate similar astronomical alignments:

- Callanish on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland features stone circles and alignments that track both solar and lunar cycles.

- The Goseck Circle in Germany, dating to approximately 4900 BCE, contains precisely aligned gates marking the winter and summer solstice sunrise and sunset points.

- The Medicine Wheel in Wyoming shows alignments to summer solstice sunrise and sunset as well as the rising points of important stars.

These circular structures share common architectural principles despite their geographic separation, suggesting that ancient societies independently discovered the effectiveness of circular design for astronomical observation. What elevates these structures beyond mere astronomical instruments is their dual function as sacred spaces. The circular form served as a perfect geometric interface between earthly rituals and celestial movements. Several key characteristics define this sacred-astronomical relationship:

- The circle creates a microcosm of the celestial dome above, allowing worshippers to symbolically stand at the center of the cosmos.

- Circular movement around these monuments mimics astronomical motion, potentially forming the basis for ritual circumambulation practices found across many traditions.

- The precise alignment of architectural elements with celestial events transforms natural phenomena into scheduled ritual occasions, embedding astronomical knowledge within religious practice.

- The circular form creates a distinct boundary between sacred and profane space, with astronomical alignments serving as temporal gateways between ordinary and sacred time.

The monuments themselves thus serve as evidence of advanced mathematical thinking, preserving this knowledge in stone for millennia before written mathematical treatises existed. This integration of mathematics, astronomy, and sacred architecture in circular forms demonstrates that our ancestors possessed a holistic understanding of these disciplines rather than viewing them as separate fields of knowledge. The circle became the geometric form that elegantly unified these domains of understanding. What makes circular sacred architecture so compelling is its ability to create experiential understanding. When a person enters a circular sacred space, the absence of corners and the equal distance to the center from all points creates a unique psychological effect—one feels embraced, contained, and centred simultaneously. The circular form subtly reminds us that we stand at the intersection of earth and heaven, time and eternity.

Sound behaves differently in circular spaces as well. The acoustics of domes and circular chambers often create unique resonance patterns that enhance chanting, prayer, and music. Some circular chambers produce whispering gallery effects where sound travels along the curved surface, allowing quiet words spoken at one point to be heard clearly at distant points—a phenomenon that seems to transcend ordinary physical laws and thus reinforces the sacred nature of the space.

In your exploration of sacred geometry, the circle in architecture reveals itself not merely as a design element but as a profound symbolic language that speaks to universal human intuitions about divinity, cosmos, and our place within it. These sacred circular spaces continue to move us because they speak to something deeply embedded in human consciousness—our intuitive recognition of wholeness, perfection, and divine order manifested through the perfect geometric form of the circle.

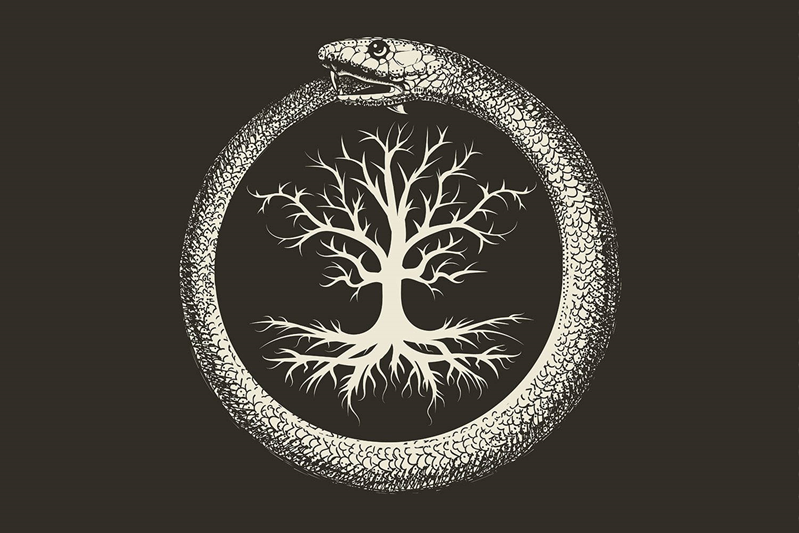

Occult teachings regard the circle as a powerful symbol, encapsulating the notion of eternity, unity, and the primordial essence of creation. With no beginning or end, the circle becomes an emblem of infinity, representing the boundless and eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth. The esoteric concept of the “ouroboros”—a serpent devouring its own tail—illustrates this infinite loop of renewal and the perpetual dance of creation and destruction.

The ouroboros—the serpent swallowing its own tail is an ancient symbol which represents cyclical nature, the eternal return, and the unity of all things. Alchemists viewed their great work as a circular process of solve et coagula (dissolution and recombination), mirroring how matter continuously transforms while maintaining underlying unity. The circular nature of alchemical transformation echoes through systems like the Hermetic axiom "as above, so below," suggesting a mirroring between macrocosm and microcosm.

Many spiritual and traditional worldviews embrace a circular understanding of time rather than the linear progression often emphasized in modern thinking. In traditional worldviews, time moves in recurring patterns rather than solely forward. This cyclical conception appears in numerous cultural and spiritual systems. Seasonal observation forms a foundation for this understanding. Agricultural societies particularly noted the reliable return of planting seasons, harvest times, and fallow periods. These natural cycles became embedded in cultural calendars and religious observances.

Solar and lunar cycles provide the basis for many traditional calendars. The moon's phases—from new to full and back again—create a visible monthly cycle. Similarly, the sun's annual journey through solstices and equinoxes demonstrates a yearly pattern of death and rebirth, particularly evident in the changing seasons. Religious festivals often mark these astronomical events, reinforcing the experience of time as circular.

In Hindu thought, the universe passes through vast cosmic cycles called kalpas, each containing thousands of yugas (ages). Each kalpa ends with dissolution (pralaya) followed by a new creation. Similarly, the individual soul (atman) passes through cycles of rebirth until achieving moksha. Buddhist cosmology describes universe cycles spanning billions of years, with periods of creation, stability, destruction, and emptiness. The Wheel of Samsara depicts the cyclical nature of existence and rebirth. In Mesoamerican traditions, particularly Mayan and Aztec, interlocking calendar systems tracked cycles within cycles, from the 260-day tzolkin to the 52-year Calendar Round to much longer cycles spanning thousands of years.

This circular understanding challenges the notion of absolute beginnings and endings. Rather than seeing events as final conclusions, a cyclical perspective recognizes that endings contain the seeds of new beginnings—just as winter contains the dormant life that will emerge in spring. The circle as a symbol perfectly captures this understanding, having no beginning or end point, only continuous motion. This differs fundamentally from the linear, progressive view of time often dominant in modern thought, where history moves from definite beginning points toward ultimate conclusions or goals. By examining these cyclical conceptions of time, we gain insight into alternative ways of understanding our place in the cosmos and our relationship with past and future generations.

Many magical traditions employ circular talismans and amulets. These objects, often inscribed with symbols, names, or numbers arranged in circular patterns, were thought to concentrate and direct spiritual energies. The circular form allowed for continuous flow of these energies, creating self-sustaining magical circuits. Medieval grimoires contain numerous examples of such circular designs, from protective pentacles to complex summoning circles used in ceremonial magic. The circle appears prominently in divinatory practices. The circular spread of tarot cards creates a symbolic space where meanings emerge through relationship rather than linear sequence.

In Western occult traditions, the circle relates to the concept of the sphere of sensation or aura—the energetic field surrounding each person. This personal circle defines the boundary between individual consciousness and the larger world. Magical training often focuses on purifying and strengthening this circular energy field, making it more receptive to beneficial influences while resistant to harmful ones. The magician learns to consciously work with this personal circle, expanding and contracting it as needed for different spiritual operations.

The spiritual significance of the circle extends into modern esoteric systems. Rudolf Steiner's anthroposophy uses the circle to illustrate the relationship between spiritual and material worlds, showing how consciousness evolves through cyclical processes of incarnation.

Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), the founder of anthroposophy, used the circle as a fundamental teaching tool to illustrate complex spiritual concepts. In Steiner's cosmology, human consciousness doesn't develop linearly but rather moves through cyclical patterns of evolution and transformation.

Steiner conceptualized human evolution as proceeding through great cycles or "epochs," each representing a different stage of consciousness development. The circular nature of this model was intentional—it portrayed how humanity continually returns to similar themes but at higher levels of understanding. This creates not just a circle but a spiral pattern of development.

In anthroposophical diagrams, Steiner often depicted:

- The physical world as the outer rim of a circle

- The etheric (life) forces as an inner concentric circle

- The astral (soul) realm as a yet more interior circle

- The spiritual (ego/I) center as the innermost point

This circular representation shows how human beings exist simultaneously in multiple "worlds" or planes of reality. The physical body exists in material space, while our consciousness extends inward toward spiritual dimensions. Particularly significant in Steiner's work is how the circle represents the process of incarnation and excarnation (death). He taught that:

- The soul descends from spiritual realms into physical incarnation

- Lives through earthly experiences

- Returns to spiritual realms

- Processes those experiences

- Eventually reincarnates to continue its evolutionary journey

This continuous cycle creates a rhythmic pattern that Steiner believed was essential for soul development. Each circuit through this "circle" brings new opportunities for growth and transformation.

The circle thus becomes a teaching tool that helps us visualize complex spiritual concepts about how consciousness moves between material and spiritual realms, how development happens through cyclical patterns, and how apparent opposites (like spirit and matter) can be understood as different points on a unified continuum rather than as separate categories.

Similarly, Carl Jung's mandala studies examined how circular images emerge spontaneously in dreams and artwork during psychological integration, suggesting the circle serves as an archetypal image of the unified self.

The Triangle △

The triangle stands as one of the most fundamental geometric shapes in human consciousness, appearing across diverse cultures, spiritual traditions, and occult systems throughout history. Its three sides and three angles form a complete, closed figure that embodies stability while simultaneously suggesting dynamic movement and transformation.

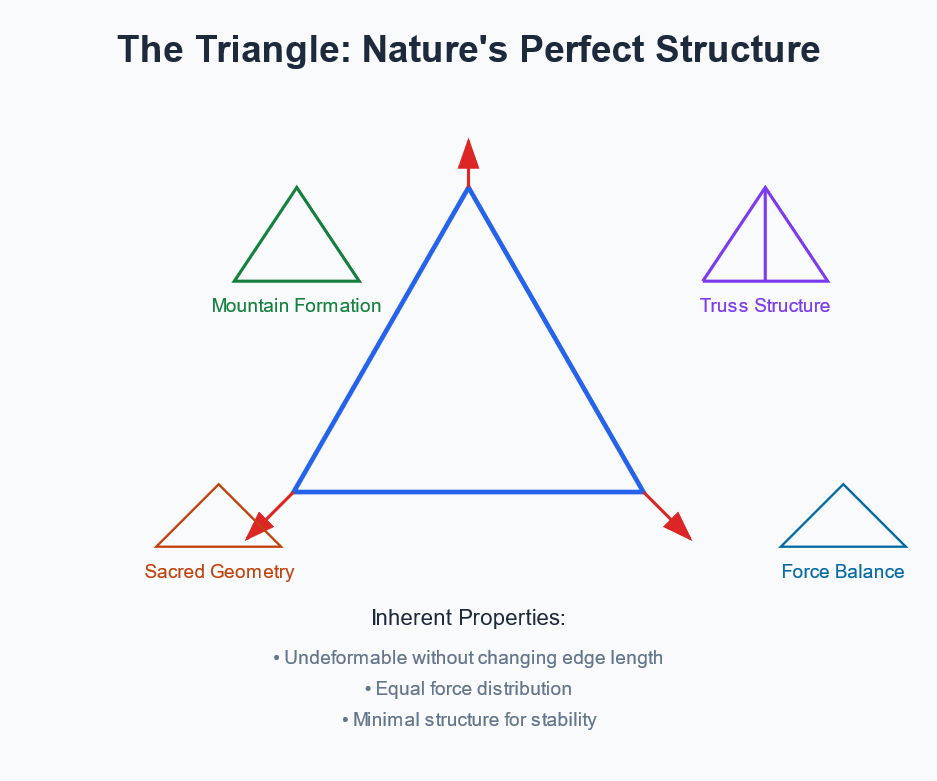

The triangle, revered as a fundamental archetype of stability, stands as nature's most efficient structure. As the simplest polygon, it holds a distinguished place in both mathematics and sacred geometry. With its three sides forming a rigid configuration that cannot be altered without changing the length of an edge, the triangle is the strongest and most stable shape. This inherent strength underlies its prevalence in both natural phenomena and human engineering feats.

In the natural world, the triangle emerges with striking regularity. It forms the structural framework of crystals at the molecular level, guides the fractal branching of trees striving toward the sun, and shapes the strategic arrangements of birds in flight for optimal energy conservation. Mountains ascend in triangular profiles, their slopes finding an equilibrium in the perfect angle of repose. Even the delicate yet resilient construction of a spider’s web incorporates triangular patterns, optimizing its strength-to-weight ratio and enabling it to withstand external pressures.

Architecture, too, has long harnessed the unparalleled stability of the triangle. From the monumental pyramids of Egypt, embodying both engineering prowess and sacred purpose, to the sophisticated space frames of modern constructions, triangles provide indispensable structural integrity. Builders of Gothic cathedrals employed triangular principles to craft soaring arches and vaults, creating spaces that seem to transcend gravity itself. Today, bridges and skyscrapers rely on triangular trusses to efficiently distribute forces, ensuring strength and stability against the forces of nature.

Beyond its physical properties, the triangle carries profound symbolic resonance across cultures. It frequently embodies divine trinities and the balance of three essential principles. The triangle represents the unity of body, mind, and spirit; the temporal flow of past, present, and future; and the cosmic cycle of creation, preservation, and dissolution. In the realm of sacred geometry, the triangle acts as a conduit between the earthly and the divine, its upward-pointing apex signifying aspiration and spiritual ascension toward higher realms of existence.

This symbolism amplifies the triangle’s role as a bridge between the tangible and the ethereal, a shape that not only supports the material world but also reflects the inherent harmony of universal principles. Through its simplicity, the triangle whispers of profound truths and serves as a reminder of the interconnected forces that shape both the seen and unseen.

The triangle's significance extends far beyond its structural properties into the realm of metaphysics and sacred symbolism. In ancient Egypt, the triangle embodied divine principles, with the Great Pyramids serving as massive three-dimensional triangles linking earth to sky. Each face of the pyramid creates a perfect triangle, oriented to the cardinal directions with remarkable precision. This alignment wasn't merely pragmatic but cosmological—the triangular faces created a stairway for the pharaoh's soul to ascend to the circumpolar stars, considered the realm of immortality in Egyptian cosmology.

The Pythagoreans, who established one of Western civilization's first mathematical-spiritual schools, venerated the triangle as the first complete shape. Their sacred symbol, the tetraktys—a triangular arrangement of ten points—represented the perfection of number and form in a single unified image. This arrangement contained four rows (1+2+3+4=10), forming a triangle that encoded musical harmonies, cosmic ratios, and the fundamental nature of reality itself. When initiates gazed upon this triangular formation, they weren't merely seeing a geometric shape but contemplating the mathematical underpinnings of the universe.

The equilateral triangle, with its three equal sides and perfect symmetry, holds particular significance in sacred traditions. This perfect equality of proportions makes it a natural symbol for trinities found throughout world religions. In Christianity, the equilateral triangle represents the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—three persons in one divine essence. Medieval churches and cathedrals incorporate this triangular motif throughout their architecture and artwork, reminding worshippers of this fundamental theological concept. The triangle here functions not merely as decoration but as a visual theology, teaching through geometric form.

In Hindu traditions, the triangular yantra serves as a focal point for meditation practices. The downward-pointing triangle, or trikona, symbolizes feminine creative energy (Shakti), while the upward-pointing triangle represents masculine consciousness (shiva-and-shakti). When these triangles interlock to form the six-pointed star of the Sri Yantra, they represent the perfect union of these complementary cosmic forces. This sacred diagram uses triangular geometry to map the process of creation itself—from unity (the central point) to multiplicity (the expanding triangular patterns).

The orientation of the triangle carries distinct symbolic meanings. The upward-pointing triangle (▲) represents fire, masculine energy, and spiritual aspiration. Its shape mimics a flame reaching upward, suggesting transformation and transcendence. In alchemical symbols, this triangle denotes the element of fire, the active principle that catalyzes change. Fire transforms matter from one state to another, just as spiritual practice transforms consciousness. This triangular symbol reminds practitioners that transformation requires direction and purpose—energy channeled with intention toward higher states of being.

Conversely, the downward-pointing triangle (▼) symbolizes water, feminine energy, and the descent of spirit into matter. Water flows downward, seeking the lowest point, yet contains the potential for life and renewal. In many tantric traditions, this inverted triangle represents the yoni, the sacred feminine principle that receives, nurtures, and gives birth to new possibilities. The downward triangle appears in the subtle anatomy of yoga as the muladhara (root) chakra, grounding spiritual energy in physical existence. This orientation reminds us that genuine spirituality must be embodied and grounded, not merely abstract or theoretical.

When these opposing triangles merge to form the six-pointed star or hexagram, they create a powerful symbol of integration and balance found across diverse traditions. In the Jewish tradition, this becomes the Star of David (Magen David), representing divine protection and the covenant between God and humanity. In Hermeticism, this same form signifies "as above, so below"—the correspondence between macrocosm and microcosm, heaven and earth, spirit and matter.

The triangle's three sides naturally lend themselves to representing tripartite concepts found throughout wisdom traditions. The three gunas in Vedic philosophy—sattva (harmony), rajas (activity), and tamas (inertia)—form the fundamental qualities that, in different combinations, constitute all existence. Similarly, in Western esoteric traditions, the triangle corresponds to the three alchemical principles—sulfur, mercury, and salt—which represent soul, spirit, and body respectively. These triangular relationships aren't merely conceptual but represent dynamic forces in constant interaction, just as the three points of a triangle maintain perfect relationship regardless of the triangle's size.

In alchemy, the triangle's three points correspond to the three primary substances: sulfur (soul), mercury (spirit), and salt (body). These principles are not just symbolic but are also seen as the essential components of all matter. Sulfur represents the active, masculine principle of transformation and vitality. Mercury, the passive, feminine principle, symbolizes fluidity and adaptability. Salt, the neutral principle, represents stability and crystallization. The alchemical process involves the purification and recombination of these elements, often visualized as a triangle within a circle, symbolizing the integration of spirit and matter.

While the three gunas—sattva, rajas, and tamas—have been mentioned, their deeper implications can be explored. Sattva, representing harmony and purity, is often associated with the upward-pointing triangle, symbolizing spiritual ascent and enlightenment. Rajas, representing activity and passion, corresponds to the dynamic energy that propels change and transformation. Tamas, representing inertia and darkness, is linked to the downward-pointing triangle, symbolizing grounding and materiality. The interplay of these gunas is not static; they are in constant flux, much like the angles and sides of a triangle that can shift while maintaining their fundamental relationship.

The triangle's three-sided structure is a powerful symbol that resonates deeply with tripartite concepts across various wisdom traditions, reflecting the universal principle of division and unity. Beyond the examples already mentioned, the triangle's triadic nature can be expanded upon in several other philosophical, spiritual, and scientific contexts, further illustrating its significance as a fundamental archetype.

In Buddhism, the triangle can be seen as a representation of the Three Jewels (Triratna): the Buddha (the enlightened one), the Dharma (the teachings), and the Sangha (the community of practitioners). These three elements form the foundation of Buddhist practice and spiritual refuge. The triangle's three sides symbolize the interdependence of these jewels—without the Buddha, there would be no Dharma; without the Dharma, there would be no Sangha; and without the Sangha, the teachings would not be preserved and propagated. This triadic relationship mirrors the triangle's inherent stability and interconnectedness.

In many shamanic traditions, the triangle represents the three realms of existence: the Upper World (the realm of spirits and deities), the Middle World (the physical world of humans and nature), and the Lower World (the realm of ancestors and subconscious forces). Shamans often journey between these realms to retrieve knowledge, heal, or restore balance. The triangle serves as a map for navigating these spiritual dimensions, with each point representing a gateway to a different plane of existence. The upward-pointing triangle may symbolize ascension to the Upper World, while the downward-pointing triangle may represent descent into the Lower World.

The triangle can also represent the threefold nature of time: past, present, and future. In many traditions, time is not seen as a linear progression but as a cyclical or triadic relationship. The past influences the present, the present shapes the future, and the future, in turn, loops back to inform the past. This triadic view of time is reflected in the triangle's structure, where each point is connected to the others, creating a continuous loop of cause and effect. This concept is particularly evident in Hindu cosmology, where time is divided into cycles (yugas) that repeat in a grand cosmic rhythm.

The triangle's representation of the threefold nature of time—past, present, and future—offers a profound lens through which to explore the cyclical and interconnected nature of temporal existence. This concept is not only central to Hindu cosmology but also resonates deeply with other spiritual and philosophical traditions, as well as modern scientific thought.

In Hindu cosmology, time is not a straight line but a series of repeating cycles known as yugas. These yugas—Satya Yuga, Treta Yuga, Dvapara Yuga, and Kali Yuga—represent different epochs of human and cosmic development, each with its own characteristics and spiritual qualities. The cycle of yugas is often depicted as a wheel, but the triangle can also symbolize the triadic relationship between the past, present, and future within each yuga.

- Satya Yuga (Golden Age): This is the age of truth and purity, where humanity lives in harmony with divine principles. The past (Satya Yuga) influences the present by setting a standard of spiritual and moral excellence.

- Treta Yuga (Silver Age): In this age, virtue begins to decline, but spiritual practices and rituals still hold great power. The present (Treta Yuga) is shaped by the past, as humanity strives to maintain the wisdom of the Satya Yuga.

- Dvapara Yuga (Bronze Age): This age sees further decline in virtue and the rise of materialism. The future (Dvapara Yuga) is influenced by the present, as humanity begins to lose touch with the spiritual truths of earlier ages.

- Kali Yuga (Iron Age): The current age, marked by conflict, ignorance, and moral decay. Yet, even in this age, the seeds of the future are sown, as the cycle eventually returns to the Satya Yuga, completing the cosmic rhythm.

The triangle, with its three points, can be seen as a microcosm of this larger cycle, representing the interplay of past, present, and future within each yuga. Each point of the triangle influences the others, creating a dynamic flow of time that is both cyclical and interconnected.

The concept of eternal return, found in many traditions, suggests that time is not linear but cyclical, with events recurring in an endless loop. This idea is particularly prominent in Nietzschean philosophy, where the eternal return is seen as a test of one's ability to affirm life in all its aspects. The triangle, with its three points, can symbolize this eternal return, where the past, present, and future are not separate but part of a continuous, repeating cycle.

- Past: The past is not something that is gone forever but a living force that continues to influence the present. In the triangle, the past is one point, constantly feeding into the present.

- Present: The present is the point where past and future meet. It is the moment of action, where decisions are made that will shape the future. The present is the fulcrum of the triangle, balancing the influences of the past and the potential of the future.

- Future: The future is not a distant, unknown realm but a direct consequence of the present. In the triangle, the future is the third point, looping back to inform the past, creating a continuous cycle of cause and effect.

This triadic view of time challenges the linear perspective that dominates modern thought, suggesting instead that time is a spiral, where each cycle brings new opportunities for growth and transformation.

Many indigenous cultures also view time as cyclical rather than linear. For example, in Native American traditions, time is often seen as a circle or spiral, with the past, present, and future interconnected. The triangle can be seen as a simplified representation of this spiral, with each point representing a different phase of the cycle.

- Past: The past is the foundation, the wisdom of the ancestors that guides the present. In the triangle, the past is the base, providing stability and continuity.

- Present: The present is the moment of action, where the lessons of the past are applied to create the future. The present is the apex of the triangle, the point of transformation.

- Future: The future is the result of the present, but it also loops back to inform the past, creating a continuous cycle of renewal. In the triangle, the future is the third point, completing the cycle.

This cyclical view of time is often reflected in rituals and ceremonies, where the past, present, and future are honored and integrated. For example, in vision quests or sun dances, participants connect with the wisdom of the past, act in the present to seek guidance, and envision a future that is in harmony with the natural world.

Even in modern physics, the concept of time as a cyclical or triadic phenomenon finds resonance. In uantum mechanics, time is not always linear; particles can exist in multiple states simultaneously, and events can influence each other in non-linear ways. The triangle can be seen as a metaphor for this complex interplay of past, present, and future in the quantum realm.

- Past: In quantum physics, the past is not fixed but can be influenced by future events, a phenomenon known as retrocausality. The past is one point of the triangle, constantly interacting with the present and future.

- Present: The present is the moment of observation, where the quantum wave function collapses into a definite state. The present is the apex of the triangle, the point where potential becomes actual.

- Future: The future is not predetermined but is shaped by the present. In the triangle, the future is the third point, looping back to influence the past, creating a dynamic, interconnected web of cause and effect.

This triadic view of time challenges the classical, linear understanding of cause and effect, suggesting instead that time is a more fluid, interconnected phenomenon.

On a personal level, the triangle's representation of past, present, and future can be a powerful tool for self-reflection and growth. By understanding how the past influences the present, and how the present shapes the future, individuals can take conscious steps to break negative cycles and create positive change.

- Past: The past is a source of lessons and wisdom. By reflecting on past experiences, individuals can gain insight into their patterns and behaviors. In the triangle, the past is the foundation, providing the knowledge needed to navigate the present.

- Present: The present is the moment of action, where individuals have the power to make choices that will shape their future. The present is the apex of the triangle, the point of transformation and growth.

- Future: The future is not fixed but is shaped by the choices made in the present. By envisioning a positive future, individuals can create a vision that guides their actions in the present. In the triangle, the future is the third point, completing the cycle and providing direction.

This triadic view of time encourages individuals to take responsibility for their actions, recognizing that the present is the point where past and future meet, and where true transformation occurs.

In many spiritual traditions, the path to enlightenment or self-realization is often described as a threefold process. For example, in the Christian mystical tradition, this path is often divided into three stages: purgation (cleansing of the soul), illumination (receiving divine light), and union (merging with the divine). The triangle's three sides can be seen as representing these stages, with each side leading to the next in a continuous cycle of spiritual growth. Similarly, in Sufism, the path to God is often described as a journey through three stages: Sharia (law), Tariqa (path), and Haqiqa (truth). The triangle serves as a visual reminder of the progressive nature of spiritual development.

In psychology, particularly in the work of Carl Jung, the triangle can represent the threefold structure of the psyche: the conscious mind, the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious. The conscious mind is the tip of the triangle, representing our immediate awareness. The personal unconscious lies just below, containing repressed memories and personal experiences. The collective unconscious, at the base, represents the shared, archetypal experiences of humanity. The triangle's structure illustrates how these layers of the mind are interconnected, with the collective unconscious providing the foundation for the personal unconscious and conscious mind.

The triangle's three sides are a profound symbol of the triadic nature of existence, reflecting the universal principle of division and unity. Whether in the realms of spirituality, philosophy, psychology, or science, the triangle serves as a reminder that reality is often structured in threes, with each element influencing and being influenced by the others. This triadic structure is not just a conceptual framework but a dynamic, living reality that underpins the fabric of existence. By contemplating the triangle, we gain insight into the deeper patterns that govern both the material and spiritual worlds, recognizing that harmony and balance are achieved through the interplay of complementary forces.

In sacred architecture, triangular forms create spaces that direct energy and attention. The pitched roofs of churches, temples, and sacred buildings worldwide use triangular structures not merely for practical purposes like shedding rain but for energetic and symbolic reasons. These upward-sloping planes guide the eye and spirit upward, creating what architectural theorists call "aspiring space"—environments that physically embody spiritual aspiration. This architectural application of triangular principles demonstrates how sacred geometry creates not just visual symbols but experiential realities that transform human consciousness through spatial relationships.

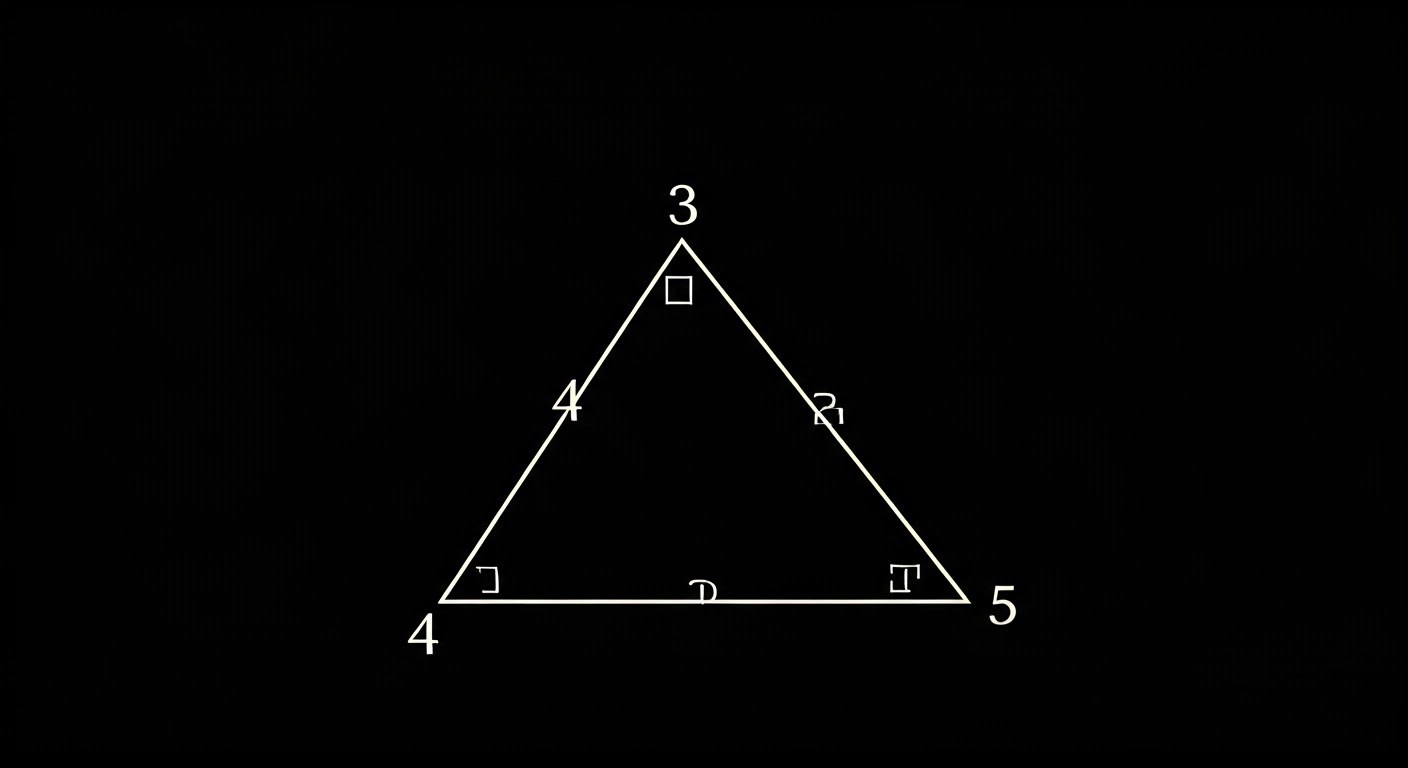

The 47th Proposition of Euclid, better known as the Pythagorean theorem, reveals another profound aspect of triangular wisdom. This mathematical principle—that in a right triangle, the square of the hypotenuse equals the sum of the squares of the other two sides—became a central symbol in Freemasonry and other Western mystery traditions. Beyond its mathematical utility, this particular triangular relationship represented the harmonious balance of opposing forces and the emergence of a third principle from their interaction. The 3-4-5 triangle, the simplest whole-number expression of this theorem, was used by ancient builders to create perfect right angles without modern measuring tools, demonstrating how abstract mathematical principles could manifest in practical craftsmanship.

The triangle also serves as an organizing principle for understanding degrees of manifestation. Numerous spiritual systems describe reality as existing on three fundamental planes—spiritual, psychic/mental, and physical. These aren't separate realms but rather different densities or frequencies of the same underlying reality, just as the three points of a triangle define a single unified shape. This triangular model helps practitioners understand how energy descends from subtler to denser forms and how consciousness can ascend through these levels through spiritual practice. The triangle thus becomes not just a symbol but a map for navigating multiple dimensions of existence.

In Sacred Geometry, the triangle generates other key forms through its movement and replication. When an equilateral triangle rotates around its center point, it creates a circle, demonstrating how straight lines can generate curved forms through dynamic motion. This principle reflects spiritual teachings about how the diversity of manifestation emerges from the rotation of fundamental patterns. Similarly, when triangles tessellate (repeat without gaps), they create honeycomb-like hexagonal patterns found throughout nature, from beehives to the molecular structure of crystals, revealing how simple forms create complex systems through repetition and relationship.

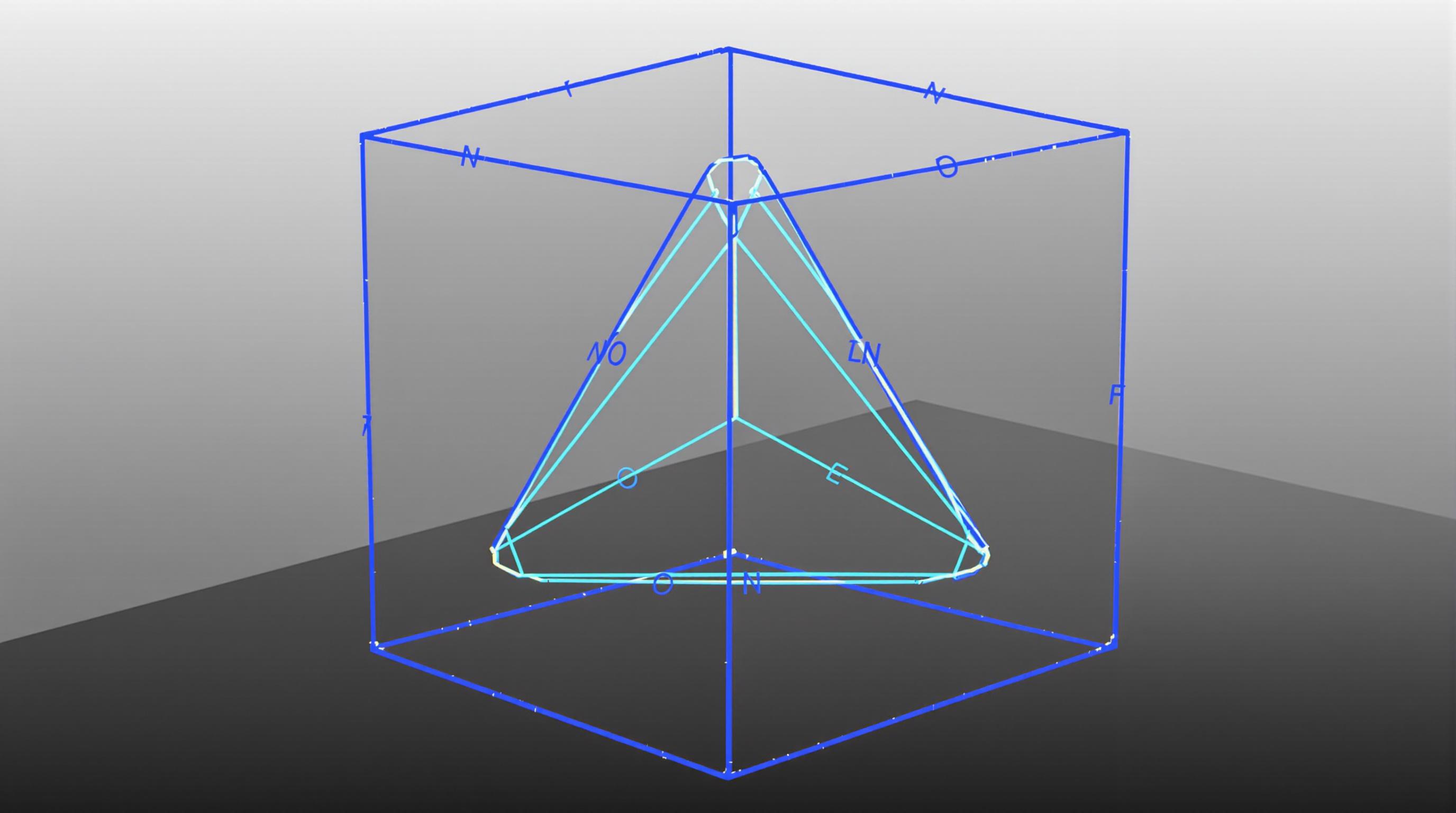

The tetrahedron—a three-dimensional triangle with four triangular faces—represents the simplest possible volume in three-dimensional space. This form corresponds to the element of fire in Platonic solid associations and represents the spark of consciousness that animates matter. Unlike other volumetric forms, the tetrahedron maintains perfect triangular symmetry when viewed from any of its vertices, embodying the principle that fundamental truths remain consistent regardless of perspective. Interestingly, the tetrahedron fits perfectly inside a cube when its vertices touch the centers of the cube's faces, demonstrating how seemingly different geometric archetypes relate through hidden harmonies.

The profound mathematical properties of triangles reveal deeper metaphysical principles. Consider the fact that the sum of angles in any triangle always equals 180 degrees, or a semicircle. This constant relationship holds true regardless of the triangle's shape or size, suggesting an underlying order that transcends specific manifestations. Similarly, triangulation—the process of determining an unknown position by measuring angles from known points—serves as both a practical surveying technique and a metaphor for spiritual discernment. By establishing clear reference points and understanding their relationships, we can locate ourselves in both physical and metaphysical landscapes.

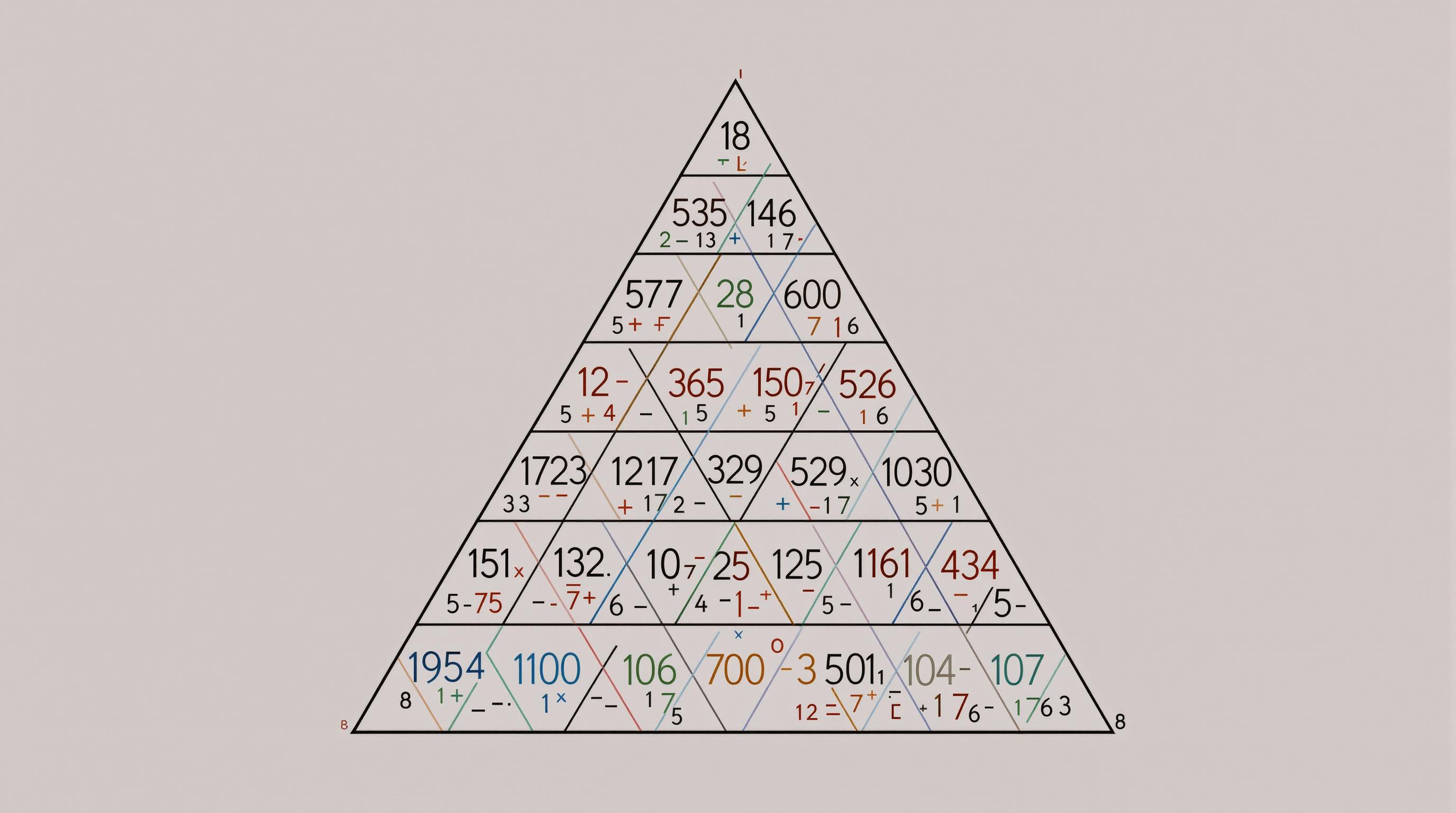

Pascal's Triangle, a triangular array of binomial coefficients where each number equals the sum of the two numbers above it, reveals the mathematical beauty of triangular patterns. This seemingly simple arrangement contains profound numerical relationships, including the Fibonacci sequence, power series, and combinatorial possibilities. The triangle reveals how new possibilities emerge from the relationship between preceding elements, mirroring how creation unfolds through the interaction of existing patterns. This mathematical triangle has been known in various forms across diverse cultures, from ancient China to medieval Persia, suggesting an archetypal quality to its revelatory structure.

In esoteric Christianity, the triangle symbolizes not only the Trinity but also the threefold nature of human existence—body, soul, and spirit. The triangle thus creates a correspondence between divine and human nature, suggesting that humanity is created "in the image" of divinity through this tripartite structure. Christian contemplatives used triangular diagrams to map the soul's journey toward union with God, with each side representing a distinct phase of spiritual development—purgation, illumination, and union. This geometric mapping of spiritual transformation demonstrates how sacred geometry provides not just symbols but practical frameworks for understanding the evolution of consciousness.

The triangle's significance extends into practical tools for spiritual practice. The triangular pendulum, suspended from a single point, creates a perfect vertical line due to gravity's pull, enabling builders to establish true vertical alignment when constructing sacred spaces. This practical application carries symbolic significance—the triangle-based plumb line represents the soul's natural tendency to seek alignment with higher principles. Similarly, triangular musical instruments like the stringed psaltery create harmonic resonances based on triangular proportions, demonstrating how geometric forms translate into audible harmonies that affect consciousness through sound.

In dream symbolism and visionary experiences, triangular forms often appear during periods of spiritual transformation. Carl Jung noted the emergence of triangular imagery in his patients' dreams during processes of psychological integration, particularly when the conscious mind was reconciling with previously unconscious material. The triangle in these contexts represents the transcendent function—the third element that emerges when opposing aspects of the psyche integrate. This psychological triangle mirrors the spiritual principle that growth often requires the reconciliation of apparent opposites to generate a higher synthesis.

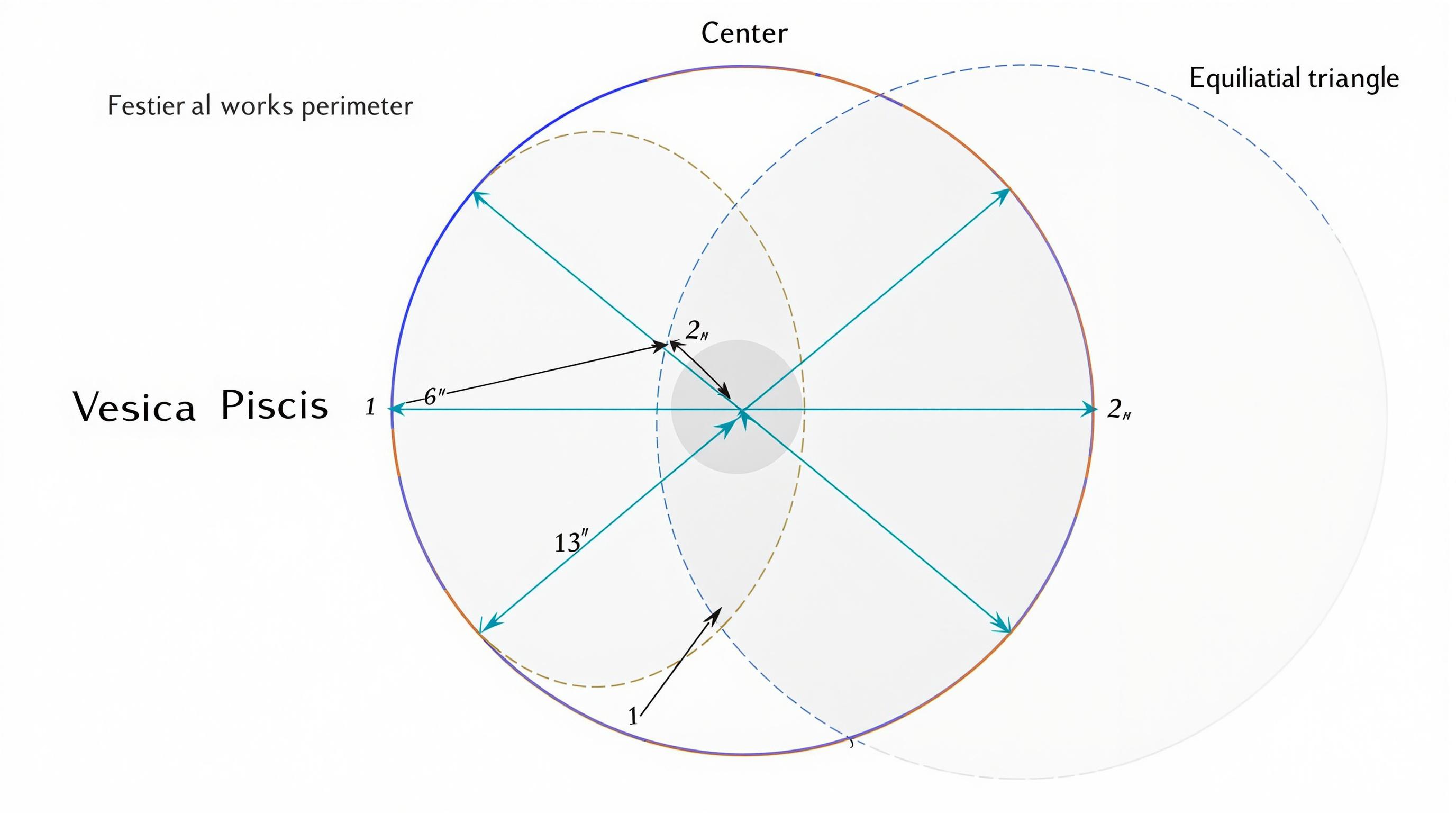

The Vesica Piscis—the almond-shaped intersection created when two circles of the same radius overlap so that the center of each circle lies on the circumference of the other—generates important triangular relationships. When lines are drawn connecting the two circle centers to any point on the Vesica's perimeter, a perfect equilateral triangle results. This geometric fact reveals how the triangle emerges naturally from the relationship between dualities, represented by the two circles. The Vesica Piscis appears prominently in sacred art as the aureole surrounding Christ and saints in Christian iconography, with its hidden triangular properties suggesting divine proportion and harmony.

In Kabbalistic teachings, the triangle relates to the three "pillars" of the Tree of Life—severity on the left, mercy on the right, and balance in the center. These three columns organize the ten sephiroth (divine emanations) into a cohesive system that maps the process of creation from divine unity to material manifestation. The triangular relationships between individual sephiroth create pathways for consciousness to move between different levels of reality. Kabbalistic meditation often involves visualizing these triangular relationships to activate corresponding aspects of consciousness, demonstrating how triangular geometry functions as a technology for spiritual development.

The triangle also represents stages of alchemical transformation. The alchemical axiom "solve et coagula" (dissolve and coagulate) describes a process that requires a third element—the container or vessel in which transformation occurs. This creates an alchemical triangle of active agent, receptive substance, and containing vessel that parallels many creation myths involving creator, created, and the space of creation. The triangle thus maps not just static relationships but dynamic processes of transformation that apply to matter, consciousness, and spirit alike.

As we contemplate the triangle in sacred geometry, we discover that its significance goes far beyond its mathematical properties. The triangle embodies the principle of stable relationship—the minimum number of points (three) needed to define a plane in space. It represents completion through the reconciliation of dualities, with the third point transcending and including the apparent opposition of the first two. It demonstrates how simplicity generates complexity through movement, repetition, and relationship. And perhaps most importantly, it reminds us that stability—whether in physical structures, philosophical systems, or spiritual development—requires at least three points of reference in proper relationship.

The triangle invites us to consider what trinities exist in our own experience—body-mind-spirit, thought-feeling-action, past-present-future—and how these tripartite relationships create the stable foundation for our ongoing growth and unfoldment. As we integrate this triangular wisdom, we develop a more nuanced understanding of both the physical and metaphysical dimensions of reality, recognizing how three-fold patterns create harmony, stability, and evolutionary potential at every level of existence.

In ancient Egypt, the triangle embodied the primordial mound that emerged from the waters of chaos at creation's beginning. This concept manifested physically in the Great Pyramids, whose triangular sides created pathways between earthly and divine realms. Egyptian priests understood that the triangular form concentrated cosmic energies in specific ways, amplifying consciousness beyond ordinary human perception. The precise angles of the Great Pyramid at Giza—51 degrees, 51 minutes, and 14 seconds—were calculated to align with stellar configurations and optimize the flow of universal life force.

In Hermetic philosophy, the triangle embodies the principle "as above, so below" - the microcosm reflecting the macrocosm. When upward and downward-pointing triangles overlap to form the hexagram (the Seal of Solomon or Star of David), they create a perfect balance between opposing forces, visually representing cosmic harmony. Hermetic practitioners meditated upon these triangular formations to internalize teachings about cosmic equilibrium, using visualization to align their personal energetic systems with these universal patterns.

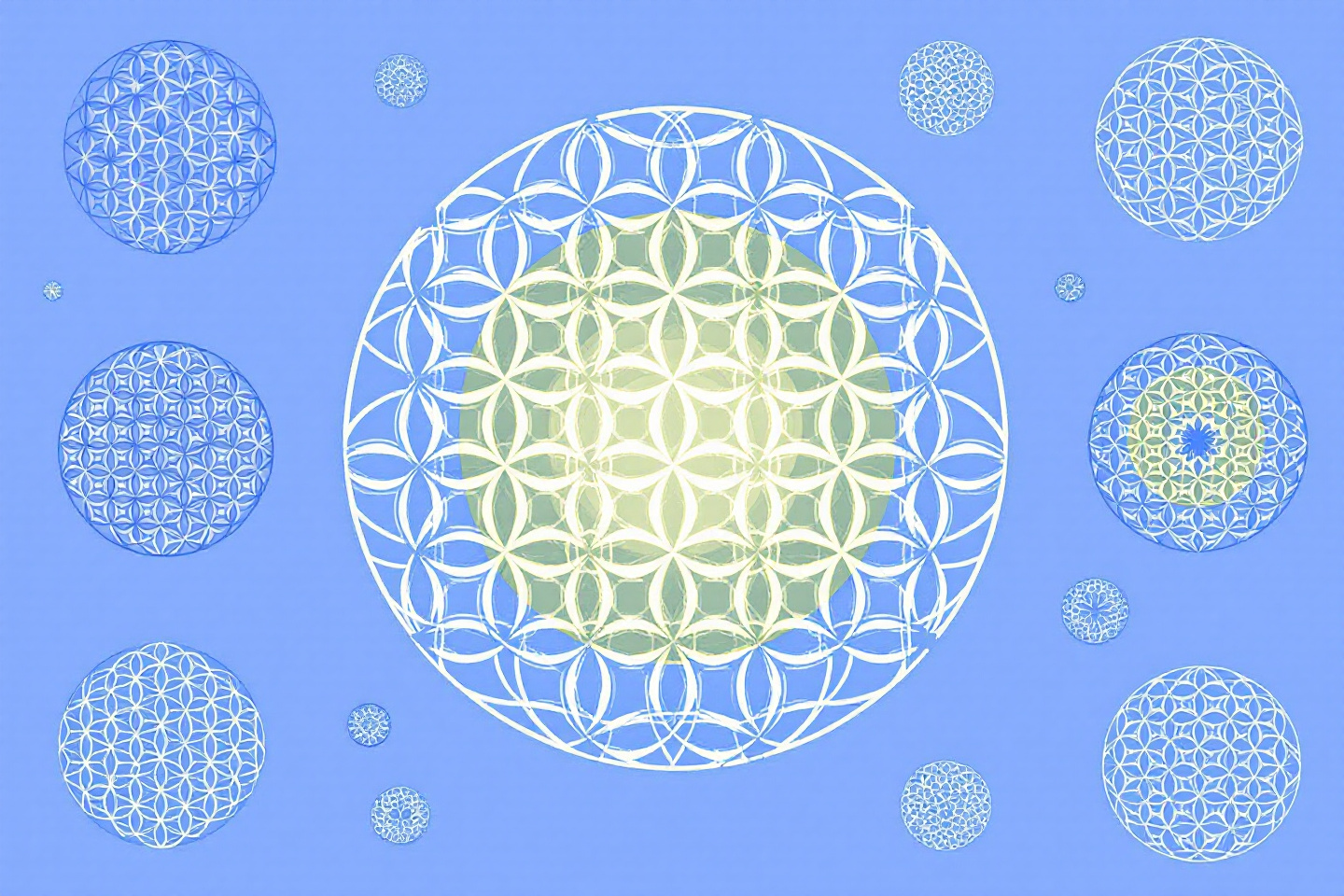

The triangle appears prominently in sacred geometry as the foundation of the Flower of Life pattern. This arrangement begins with a single circle, around which six identical circles are placed with their centers on the original circle's circumference. This creates multiple overlapping triangles representing the interconnectedness of all creation. The Flower of Life appears in ancient sites worldwide, suggesting universal recognition of the triangle's fundamental significance. Sacred geometers understood that these triangular relationships encoded vibrational patterns resonating with reality's structure. By reproducing these patterns in art, architecture, and ritual objects, they created harmonic environments facilitating spiritual awareness and healing.

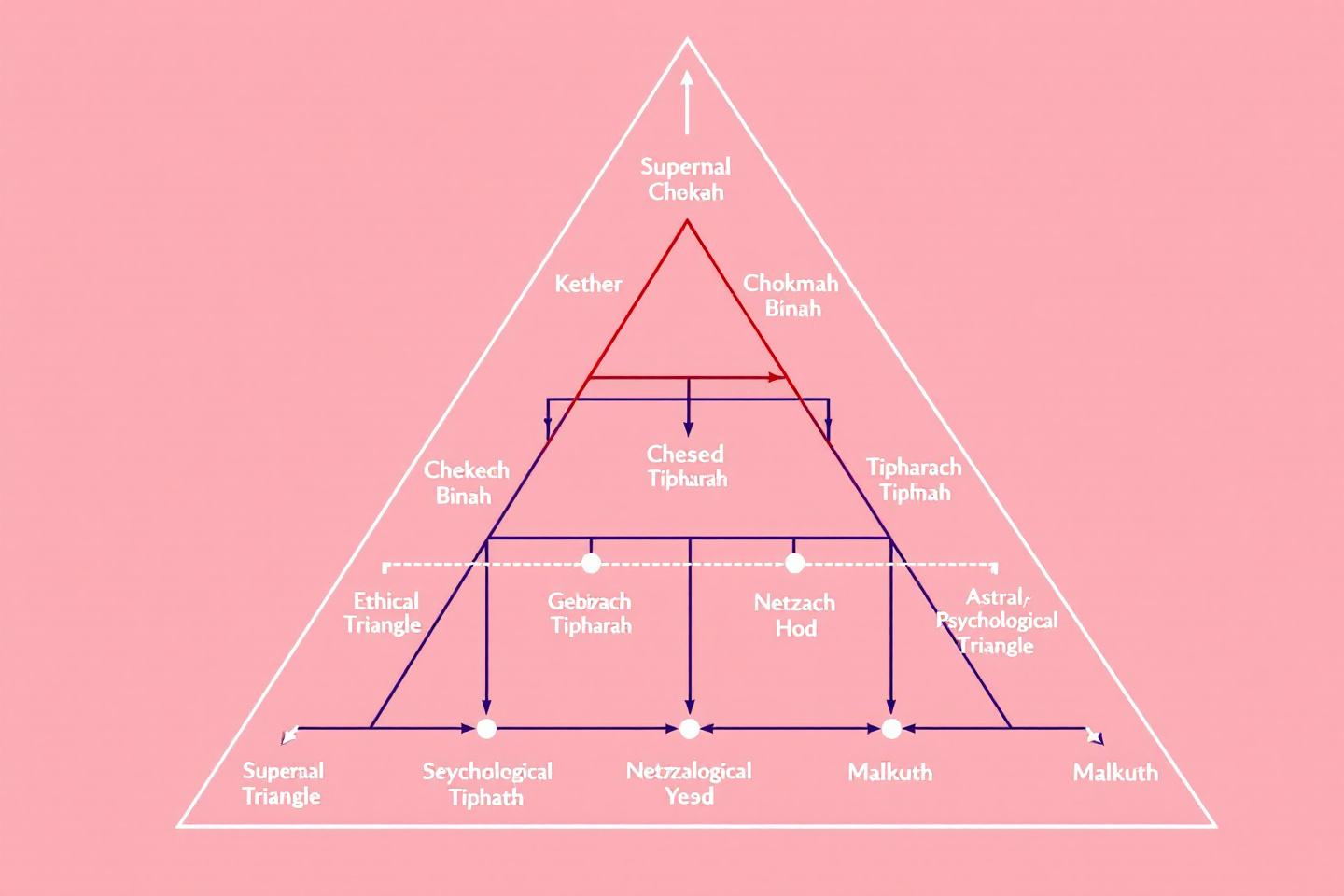

In Kabbalistic tradition, the triangular structure of the Tree of Life maps divine energy's emanations into the material world. The ten Sephiroth (divine attributes) are arranged in three columns, forming multiple triangular relationships representing different aspects of divine manifestation. The uppermost triangle, comprising the first three Sephiroth, represents the highest level of divine emanation. Kabbalistic meditation involves traversing these triangular pathways in visualization, allowing practitioners to attune their consciousness to specific divine qualities. The three supernal Sephiroth—Kether, Chokmah, and Binah—form the Supernal Triangle, representing divine consciousness beyond ordinary human comprehension. Below this, two additional triangles form: the Ethical Triangle (Chesed, Geburah, and Tiphareth) and the Astral or Psychological Triangle (Netzach, Hod, and Yesod), each encoding specific spiritual lessons and evolutionary challenges.

Esoteric traditions have long employed the triangle in ritual contexts. Ceremonial magicians use triangles of manifestation to contain and control summoned energies. The triangle serves as a focusing lens for magical intent, its three points creating boundaries that both contain power and direct it toward specific purposes. Practitioners often place the triangle within a protective circle, creating a safe space for interaction with otherworldly forces. The triangle's sharp angles are thought to create energetic "cutting points" that pierce through veils separating ordinary reality from subtler dimensions, allowing controlled interaction with these realms.

In Freemasonic symbolism, the triangle often contains the all-seeing eye, representing divine providence and the Great Architect of the Universe watching over human affairs. This symbol, which later appeared on the Great Seal of the United States, connects divine awareness with triangular structure, suggesting spiritual insight requires balanced integration of multiple perspectives. Masonic traditions teach that the triangle represents the triad of thought, feeling, and action necessary for balanced human development. The triangle surmounting a square or cube represents divine consciousness overseeing material existence, reminding initiates of the spiritual dimension infusing all worldly activities.

In tantric traditions, the downward-pointing triangle represents the yoni, the feminine creative power at the spine's base. Through meditation, practitioners seek to raise this energy through the chakras toward union with masculine consciousness at the crown, creating a spiritual energy circuit that transforms consciousness. In Tibetan Buddhist tantra, triangular visualizations assist practitioners in transforming ordinary perception into divine vision. The triangle (trigug in Tibetan) represents the three doors of liberation: emptiness, signlessness, and wishlessness. By meditating on triangular forms, practitioners gradually release attachment to conventional reality and cultivate direct perception of phenomena's ultimate nature.

The triangle manifests in numerous divinatory systems. In astrology, the trine aspect (planets 120 degrees apart) represents harmony and flow between planetary energies, forming equilateral triangles in the horoscope chart. The grand trine—three planets positioned at an equilateral triangle's vertices—indicates natural talents and harmonious expression across three areas of life. Advanced astrological practice involves analyzing multiple triangular relationships within birth charts, revealing hidden energy flow patterns and potential development paths. In the I Ching, the eight trigrams consist of three lines each, representing various yin and yang energy combinations describing existence's fundamental patterns.

The triangle's occult significance extends to geomantic systems worldwide. Ancient cultures recognized that triangular arrangements of sacred sites created energetic networks across landscapes. In Chinese feng shui, practitioners analyze triangular relationships between landforms to assess energy flow and balance. European geomancers identified triangular connections between megalithic sites, churches, and natural features that amplified Earth energies and created harmonious environments. Modern Earth mysteries practitioners continue discovering and working with these triangular alignments, finding they often correspond to ley lines and other subtle energy currents. These triangular networks serve as focal points for ceremonies intended to heal and balance planetary energies, with practitioners often physically tracing these triangular paths as pilgrimage and attunement forms.

The triangle's appearance in visionary and psychedelic experiences across cultures throughout history suggests connection to fundamental consciousness patterns. Reports from ayahuasca ceremonies, DMT experiences, and deep meditative states describe encounters with intelligent, geometric entities communicating through triangular patterns and structures. These accounts raise questions about the relationship between geometric forms and consciousness—perhaps the triangle represents not merely a human symbolic construction but an actual structural component of reality becoming perceptible in altered states. The repeated appearance of triangular forms in visionary experiences of individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds with no prior exposure to esoteric teachings suggests these forms may be intrinsic to consciousness architecture itself.

The triangle's appearance in crop formations worldwide adds another layer to its metaphysical significance. Complex geometric patterns incorporating multiple triangular elements have mysteriously appeared in fields across the globe, often near ancient sacred sites. Regardless of origins, these formations have measurable consciousness effects, with many visitors reporting altered states, healing experiences, and enhanced intuitive abilities within them. The triangular components seem to function as energy accumulators and transmitters, creating coherence fields affecting both biological systems and consciousness. Researchers have documented unusual electromagnetic readings, cellular plant changes, and crystalline soil sample alterations from these triangular formations, suggesting interaction with currently unrecognized energetic forces.